Essay by Thomas Li

sbestos exists within the memory of Australian society as a sort of spectre, a ghoul that haunts an old shed in the shaded depths of a backyard, or the attic crawlspace amongst accumulated piles of domestic junk. Neither forgotten nor present it endures within the Australian urban fabric.

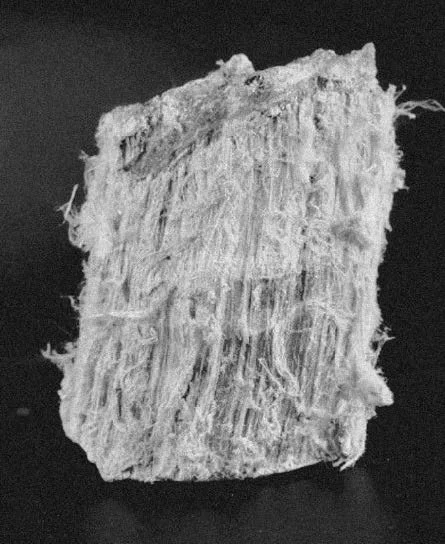

Asbestos was a material of utopian potential and ambition. It exists as a dense collection of microscopic fibrous silica crystals, in natural abundance on every inhabited continent of our planet. Its chemical properties make it inert and fireproof, its fibrous composition results in it being an anomalously effective insulator, and a strengthening agent when combined with other mediums.

The tragic narrative of asbestos in modern history sees these wondrous properties exploited by corporations on an industrial scale. As we understand clearly now, disturbed asbestos releases invisible airborne silica fibres that embed themselves into clothing, skin, and most critically, lung tissue. With no safe threshold of exposure, these fibres work covertly over the span of decades within the body creating a scarring and inflammation of the lungs leading to lung cancer, mesothelioma, and pulmonary heart disease. Symptoms of 'Asbestosis' were identified as early as 1898 by British factory safety inspectors, with the first recorded deaths confirmed in 1906. It is a condition with no cure and acts indiscriminately, yet somehow still manages to disproportionately affect the economically disadvantaged. Corporate greed and hubris were left unchecked, allowing a wilful installation of an enduring poison into the urban environment. The long dormancy of asbestosis was exploited by industry to misdirect the public eye and prolong the use of the material, knowingly sacrificing human lives and public health on a generational scale for profit.

Australia has had a troubled relationship with asbestos. In the post-war era, the rapidly growing country exhibited one of the highest rates of asbestos use per capita in the world up until the 1980s. Between the years of 1930 and 1983 alone, 1.5 million tonnes of asbestos were imported into the country in addition to Australia's own domestic production. Crocidolice and Chrysocile forms of asbestos were mined in Western Australia, New South Wales, and South Australia. Wittenoom Gorge in WA became Australia's main domestic source of Asbestos. Excavation began in 1936 and was operated by the Colonial Sugar Refinery (CSR) for three decades.

To date, over 2000 workers and residents of the cumulative population of 20,000 of Wittenoom have passed away from asbestos-related diseases. Indifferent to the increasing death toll of the citizens of Wittenoom, CSR ceased mining operations on the last day of 1966, citing the lack of profitability and falling prices of asbestos.

Australia outlawed the manufacturing and use of asbestos in 2013 on the 31st of December, 98 years after the first recorded asbestos-related death. The NSW Government now estimates that four thousand Australians pass away from asbestos-related disease annually. This is more than double the national road toll.

After five decades of prolific use, asbestos has left an entire generation of buildings and infrastructure contaminated, with one-third of Australian homes containing asbestos materials. The process of removal and remediation has been fraught with challenges. The procedures and precautions necessary to safely remove and dispose of asbestos demand a high monetary investment. The discovery of contamination can significantly drive down the market price of a home, or add to the price of a renovation. Despite strict contemporary laws and fines, the prohibitive expense of creating asbestos disincentivises or entirely prevents remediation for a large portion of the population. As a result, many Australians instead take a wilful blind eye to the risks and take a chance with asbestos. ’DIY’ removal and illegal dumping remain common in Australia, further dispersing the contamination into the land within lower income areas as affluent suburbs progress toward an asbestos-free era.

In Sydney, this manifests as an informal zone known as the 'Asbestos Belt', stretching from Sydney's Inner West out towards the Blue Mountains. Within this belt, asbestos hotspots are found to lie in correlation to areas of lower household incomes and greater ethnic diversity. As a result, asbestos remains an unresolved narrative with major incidents surfacing with regularity. The beginning of 2024 saw the discovery of asbestos debris in an Inner West playground by a child, leading to the quarantine of over 300 sites, the largest investigation in the history of the EPA. 79 sites were found to be contaminated, resulting in 102 charges filed against the offending companies. Even with such catastrophic reminders exploding into the news cycle, the magnitude of consequences will remain unknown for several decades, obscuring the poignancy of the message. Victims will remain unknowing, leaving their ability to pinpoint fault and demand justice confused by the passage of time. Asbestos will soon slip back under the surface of the public consciousness, allowing its silent threat to persist for generations to come.

A

'The Asbestos Pit': 2023 study by Thomas Li,

Kleopatra Ananada and Jasmine SharpMaps based on 2023 study by Thomas Li,

Kleopatra Ananda and Jasmine Sharp.Asbestos Belt, Western Sydney.Culturally Diverse HouseholdsLow Income HouseholdsReferences

“Toxicological Profile for Asbestos,” Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, archived September 3, 2001, at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK597327/ “History of Asbestos,” Asbestos Safety, accessed September 15th, 2025, https://www.asbestossafety.gov.au/history-asbestos Matthew Soeberg, Deborah A. Vallance, Victoria Keena, Ken Takahasi, and James Leigh, “Australia’s Ongoing Legacy of Asbestos,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no.2: 384. Jane Garnett, “Wittenoom: A Town Destroyed by Asbestos,” Maurice Blackburn Lawyers, https://www.mauriceblackburn.com.au/blog/?topic=mbl:topics/asbestos-and-silica-dust-diseases. A W Musk, N H de Klerk, A Reid, G L Ambrosini, L Fritschi, N J Olsen, E Merler, M S T Hobbs, G Berry, “Mortality of Former Crocidolite (Blue Asbestos) Miners and Miller at Wittenoom,” Occupational Environmental Medicine 65, no.8:541-3. “Asbestos in NSW,” NSW Government, accessed September 28th, 2025, https://www.asbestos.nsw.gov.au/health-risks/asbestos-related-health-conditions “National Asbestos Profile,” Australian Government - Asbestos Safety and Eradication Agency, accessed October 1, 2025, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.asbestossafety.gov.au/sites/asea/files/documents/20 17-12/ASEA_National_Asbestos_Profile_interactive_Nov17.pdf. “Asbestos in Mulch Investigation,” NSW EPA, accessed October 5th, 2025, https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/Working-together/Community-engagement/updates-on-issues/asbestos-in-mulch-investigation.